The persistence of alignment between voting intentions and self-identified national identity on the Moreno scale, as explored in Part One of this blog, warrants further exploration. It is important to understand whether national identities carry meaning of social, economic and political values beyond the ideas of nation and national interest identified in other studies. If national identities do carry such values, it may help explain why national identities are mobilised in different ways by different political parties and forces.

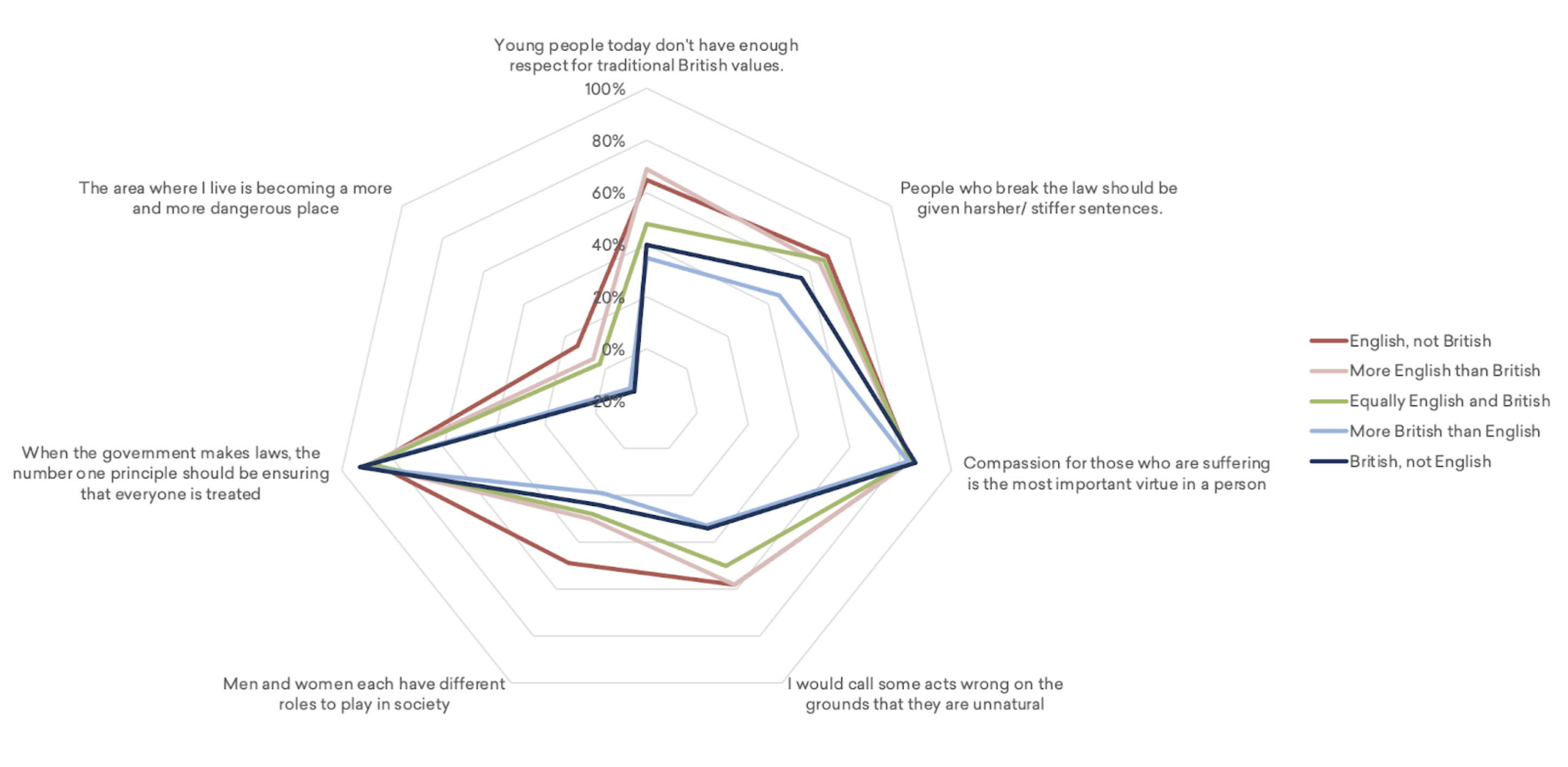

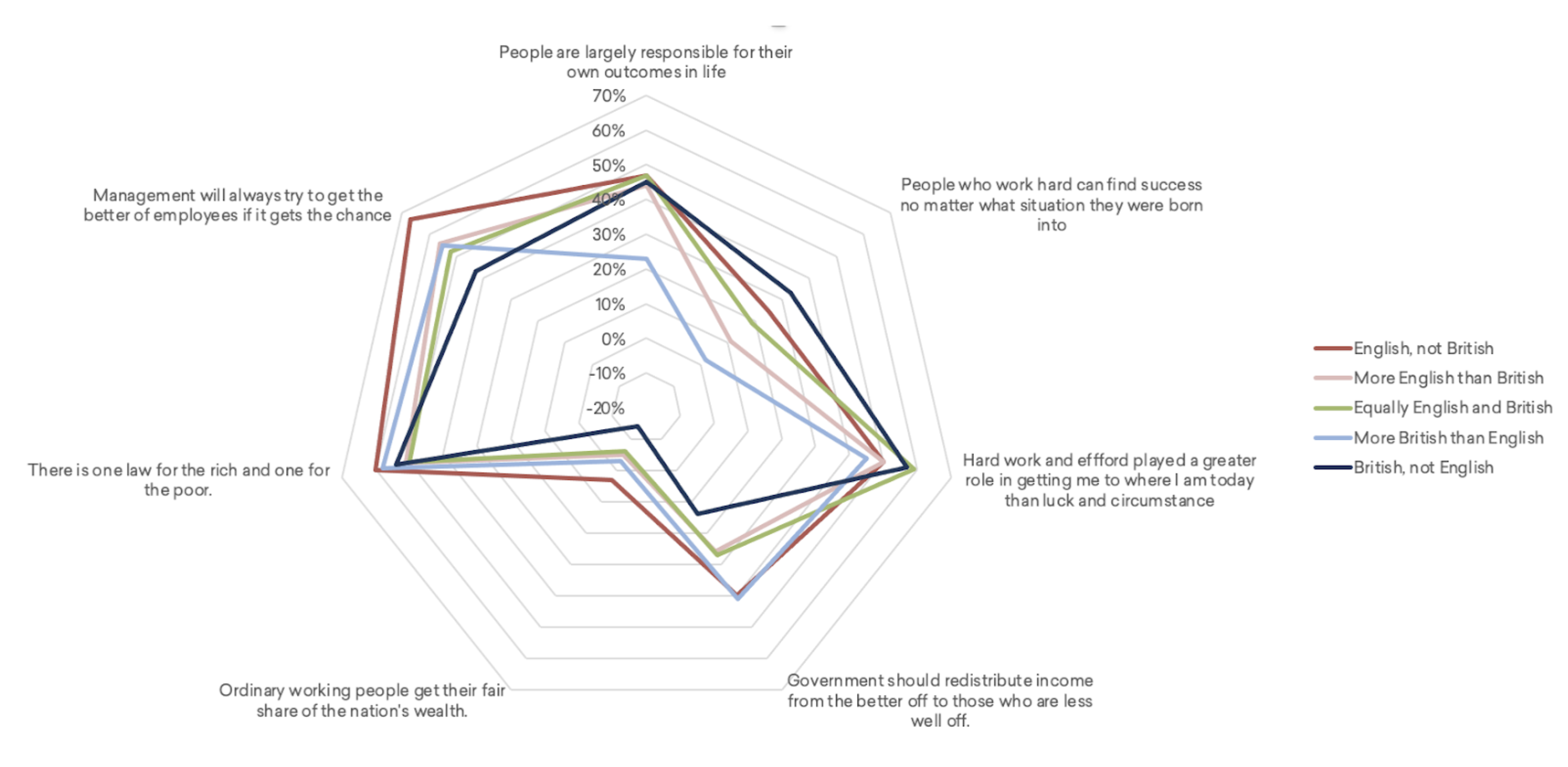

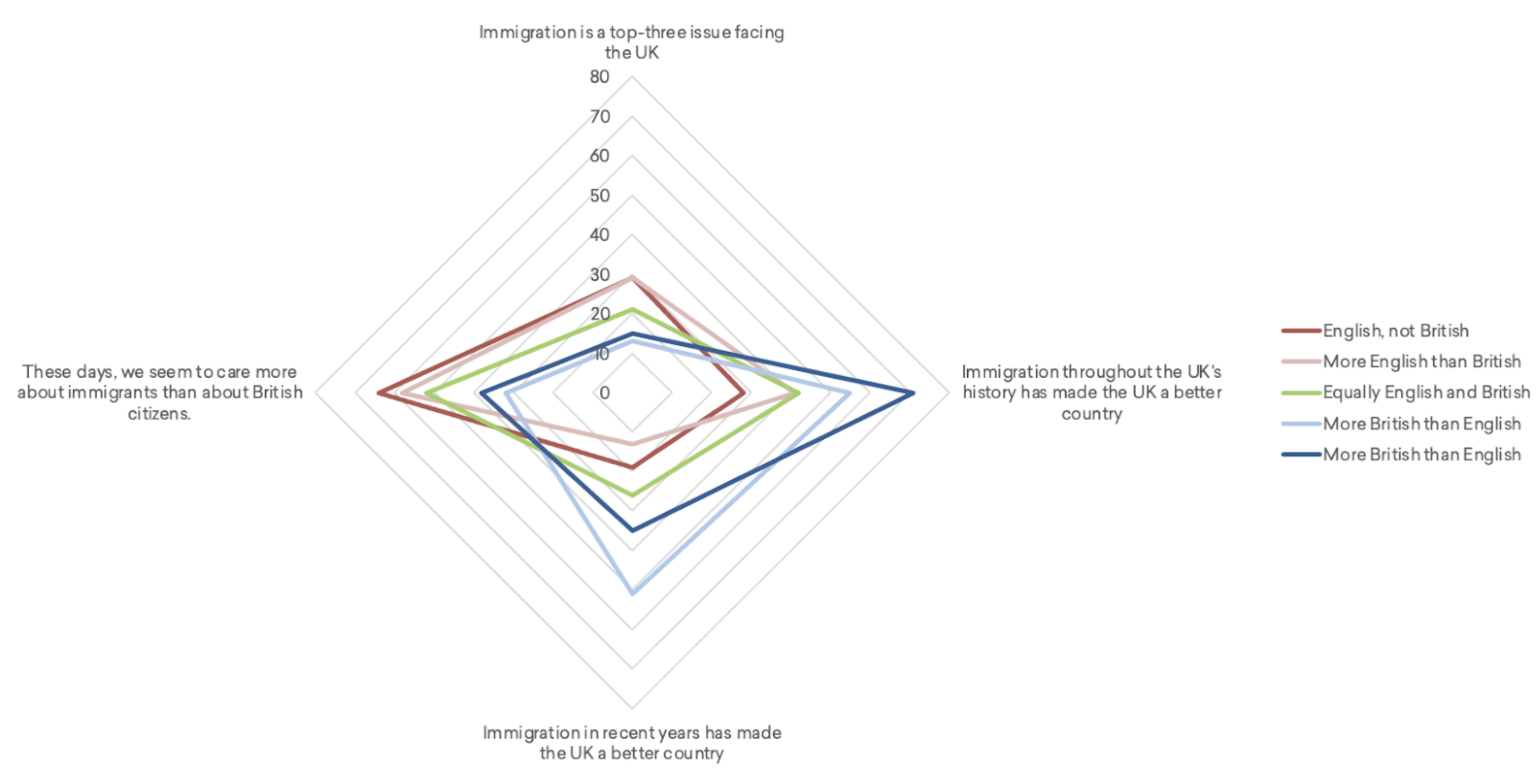

More in Common’s British Seven identifies 7 values-based segments amongst England’s population. By cross-referencing the views of voters in those segments against their position on the Moreno identity scale we explored whether different segments aligned with different national identities. We were also able to analyse the original More in Common data on the intensity and pride (‘patriotism’) in English and British national identity shown by different segments. We also examined how national identity groups responded to the key moral foundation issues that shaped More in Common’s segmentation.

The chart above summarises how each segment is divided by different Moreno national identities.

Some segments do lean more to one identity than another, but there is no segment which is overwhelmingly composed of a particular English identity group. Progressive Activists and, to a lesser extent, Civic Pragmatists and Established Liberals are more British than the average while Loyal Nationals, Disengaged Traditionalists and Disengaged Battlers tend to be more English. The segments most polarised with regards to each other – being both more British and less English or vice versa – are the British leaning Progressive Activists and the English leaning Loyal Nationals.

At the same time all identity groups, including the equally English and British, are represented in all segments. The extent to which ideas of either Englishness and Britishness on the Moreno scale represent a broader set of political, social and economic values would seem quite limited.

On the other hand, the differences are sufficient to influence the make-up of each identity group. If political, social, or economic choices appeal more to one segment than another, it will be reflected in differences in the behaviour of each identity group without necessarily being a direct reflection of national identity per se.

The chart below illustrates how two of the national identity groups are composed by segments.

The Backbone Conservative group contributes equally to both, reflecting how this group is not defined by a specific English identity. The distinctive difference between these two illustrative segments is the greater weight of the Loyal Nationalists and the Disengaged Traditionalists amongst the English not British and the greater contribution of the Established Liberals, Civic Pragmatists and Progressive Activists to the More British than English.